Where and when: Nguma Island Lodge Okavango, Okavango Delta, September 2025

On the Mokoros

0830: Today, we are setting out to explore the lagoon the traditional way, on a Mokoro; a slender dugout canoe that has shaped life in the Okavango Delta for generations.

Traditionally, Mokoros used to be carved from the yellow-wood tree. Now most are made of fiberglass: lighter, sturdier, and far less absorbent. Our guide’s pole, though, is still traditional and made of eucalyptus.

After a safety briefing (“stay seated and as still as you can, keep your centre of gravity low, if any bugs land on you, don’t panic, because the Mokoro could topple and what’s under the water is almost always worse than what’s above it”) and life jackets, we board the Mokoros.

We are traveling in the Mokoros from the lodge onto an island for a nature walk. We are traveling through marshy papyrus fields, on “hippo channels”.

According to our guide, the Okavango delta is home to about 25000 hippos. During the day, hippos stay cool in the deeper lagoons. At night, they make their way on to islands on the delta. They follow the same routes over and over through the papyrus fields, carving channels. These channels are the backbone of the delta.

As we drifted along the channels, our guide pointed out the other forces shaping one of Africa’s last great wetlands.

Elephants are the landscapers here, knocking down trees, creating clearings, dispersing seeds, and opening paths that other species soon depend on. In the delta, elephants aren’t just residents; they’re architects.

The tiny termites also play a big role is the maintenance of the delta. Termites break down plant material, enrich the soil, and aerate it. Over decades, their mounds become islands—tiny beginnings that eventually grow into the solid patches of land scattered through the Okavango.

The delta is also full of bird-life. Some nests sit like chandeliers at the very tips of branches. The entrance is cleverly at the bottom, making life much harder for snakes looking for a meal.

Island Nature Walk

1100: After about an hour and a half on the Mokoros, we stepped out onto one of the sandy islands for a short walk. We saw a few antelopes in the distance, but nothing bigger (good thing too – see my postscript below).

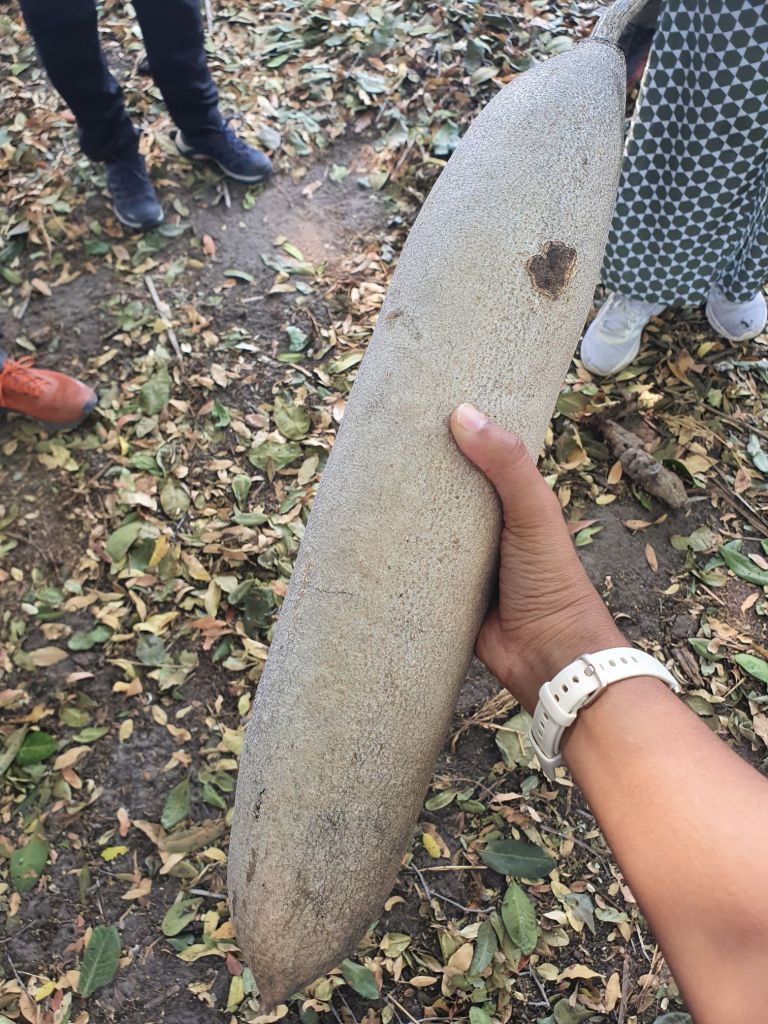

On the walk, the guide pointed out plenty of fresh elephant and hippo foot prints and dung, birds and various plants. A particularly large sausage tree stood out. The fruit is very heavy. Locals use its fibrous material to make loofahs.

In the old days, the fruit even served as a trap for crocodiles—their teeth would snag in the fibrous pulp. Ground into a paste, parts of the fruit are traditionally used to treat certain skin conditions.

The guides also discussed the effect of climate change on the the delta. Lack of rainfall leads to less water on the Okavango coming in from Angola. This could lead to the delta drying out, upending many ecosystems. It will also change the tourist trade as the hippo channels disappear and small islands separated by shallow water become to larger land masses. With no hippo channels, Mokoro safaris will be replaced by land safaris.

After about an hour on the island, we headed back, the same way we came. On the way the Mokoros did get stuck on the shallows, needing a few pushes to get us through.

We spent the rest of the day at the lodge relaxing, enjoying the breeze from the lagoon.

Post Script: Just a week after we had done this Mokoro safari, there were news reports of tourists in another part of the Okavango Delta being attacked by a bull elephant whilst on the Mokoros. According to the report, the Mokoros had gotten too close to a herd of elephants. Several people were trampled by the elephant who were trying to protect the young. It was sheer good fortune that no one died, but a sharp reminder that out in the nature, us humans are not in charge.

I know (very distantly) someone who was attacked by an elephant while on safari in Africa. I can’t remember the circumstances because it was decades ago, but I’m sure it happens more than we hear about. Glad you were okay. And don’t freak out and upend the boat because what’s below the water is worse than what’s above it?! That would make for one very uneasy ride for me!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely – then only told us that once we had settled in the boat – not sure I would have gone otherwise!,

LikeLiked by 1 person